ShopDreamUp AI ArtDreamUp

Deviation Actions

So I put it to my Patrons what the next video in this series should be, and they picked tariffs. Tariffs are basically taxes on imported goods where there isn't a corresponding tax on domestic goods, also known as "import duties" or "customs duties." With our new president promising to use tariffs to give us an advantage over other countries like China and Mexico, it's more important than ever for statists who support tariffs to formulate their arguments so they are convincing to reasonable people—which, as usual, is what they haven't done.

By the way, this video will be from an American perspective, but the concepts are universal and apply everywhere. So if you're somewhere else in the world, just replace "America" with your own country and it still applies.

This issue is very much tied in with economics, so fair warning: there's a good bit of economics in this video, but it's important. So here are the things you need to keep in mind if you want to support tariffs:

In the supply/demand model, increased costs push the supply curve to the left, meaning that producers can't produce as many items of a certain good at each price level as they could before. This increases the equilibrium price while decreasing the equilibrium quantity.

In the supply/demand model, increased costs push the supply curve to the left, meaning that producers can't produce as many items of a certain good at each price level as they could before. This increases the equilibrium price while decreasing the equilibrium quantity.

Tariffs are a cost that have to be added to the sale price of the imported good. So the only difference they'll make is in higher prices and fewer consumer goods sold.

The economic data backs this up. According to a 2008 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research:

In the early 19th century, economist David Ricardo posited the Law of Comparative Advantage. It's one of the few effects in economics that is accepted pretty much in every school of economics. To see how it works, let's simplify things a bit.

In the early 19th century, economist David Ricardo posited the Law of Comparative Advantage. It's one of the few effects in economics that is accepted pretty much in every school of economics. To see how it works, let's simplify things a bit.

Let's say there are only two people in the world. Let's call them "Adam" and "Steve." They're going to need things to survive. We'll focus on two things: spears to hunt food, and axes to chop wood for fire and shelter.

Adam can make axes more easily than spears, and Steve can make spears more easily than axes. So they decide to have Adam make the axes and Steve make the spears. They then trade an axe for a spear. If that sounds like simple division of labor to you, you're absolutely correct. And if you're thinking you have all of the advantages that come from that, like specialization, you're also correct. But there are two counterintuitive things that Ricardo and others who built on his work observed.

Let's say Adam can make an axe in 3 hours and a spear in 4, and Steve can make a spear in 1 hour and an axe in 2. So Steve can make an axe and a spear in the same time it takes Adam to make just an axe. It may sound as if Steve doesn't need Adam and Adam's going to lose out, and a lot of policies—including tariffs—are made around this misunderstanding.

But it doesn't matter. If they make the trade, then Steve only has to work two hours making two spears; it's still beneficial for him to trade with Adam. By trading, Adam only has to work 6 hours instead of 7, and Steve only has to work 2 hours instead of 3. They both save an hour of labor, and so it's beneficial to make the trade, even if Steve is better overall at making both.

The second is that this doesn't just apply to cavemen making axes and spears. It applies to everyone in a modern economy, and—this is the important part—it applies to countries as well. If Japan is better at making cars than airplanes, and America is better at making airplanes than cars, then both countries are better off if America just makes planes to sell to Japan, and Japan just makes cars to sell to America. So in such a case, putting a tariff on cars hurts Americans.

Now, you might be thinking that it has to be equal for this to work out. If Americans buy lots of Japanese cars but Japan only buys a few airplanes, Americans will lose out. But the next thing you need to do is:

If America buys millions of Japanese cars but only sells hundreds of airplanes to Japan, you might call that a "trade deficit" and say it's a bad thing. This is just a non-starter of an argument. There is no such thing as a trade deficit.

If America buys millions of Japanese cars but only sells hundreds of airplanes to Japan, you might call that a "trade deficit" and say it's a bad thing. This is just a non-starter of an argument. There is no such thing as a trade deficit.

Let's leave money out of it for a second. If we're trading airplanes for cars, then it just means that we'll trade (say) ten thousand cars for one airplane. Like Adam and Steve before, even if Japan can make an airplane for the same resources it can use to make ten thousand cars or even less, both countries are still better off making the exchange.

But it doesn't even have to be that way since countries are trading in their currencies. When Japanese want to buy an American plane, they need US dollars to do it, which means they'll have to give up some of their Japanese yen for them. And Americans who want to buy Japanese cars will need to give up some of their dollars for yen. And in the real world, of course, this happens across every product both countries trade.

For all the trade that's going on, if Japanese need 1 million dollars to buy American goods, and Americans need 1 million yen to buy Japanese goods, the exchange rate will be 1 dollar to 1 yen. But let's say there's a "trade deficit," where the amount of goods Americans buy from Japanese is more than what Japanese buy from Americans. So Americans need 2 million yen whereas Japanese still just need 1 million dollars. Now the exchange rate is 2 yen to 1 dollar. Any imbalance between trade is adjusted for by the exchange rate. And when government tries monkeying with the exchange rate, bad things happen, like in Venezuela.

But that's not what politicians are actually referring to when they talk about a trade deficit. They look at it after the exchange rate has taken place: where the exchange rate is still 2:1, but Japanese are buying less than 1 million dollars of American goods. You may be thinking, "Then what are they wanting the rest of the money for?" That is exactly the question you should ask—but it's one that politicians and the news media never seem to want to discuss.

There are only two things that can be done with money: it can be spent, or it can be invested. So if they don't want that money to purchase American goods, they must want it to invest in American capital. That means they'll be providing funds for businesses to expand, or for people to buy houses, or whatever. Investment is also known as deferred gratification, meaning in this case that Japanese are going to do less consuming, putting off some of that wealth until a later point in time, so Americans can take advantage of it.

Economists actually refer to a "trade deficit" as "net foreign investment." Because as long as exchange rates are free to fluctuate, any imbalance must be due to more investors in one country investing in the other than is going the other way. So whenever you use the term "trade deficit," understand that we see it for what it is: investment coming from other countries to expand our economy and our businesses, creating jobs and allowing us to produce more and have more for ourselves than we would have otherwise. They're doing without for a little while so that we can have more. You're going to have a very hard time convincing us that this is a bad thing.

In Chapter 6 of Economic Sophisms, Frédéric Bastiat wrote:

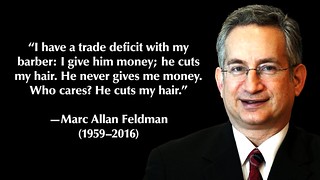

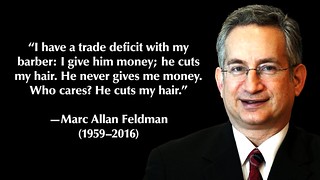

As the late Marc Allan Feldman said:

There aren't many things that economists of every school believe. So when you do get one, it's time to take notice. Every single school of economics agrees that free trade makes a country prosperous and that any kind of tariff makes the nation poorer.

There aren't many things that economists of every school believe. So when you do get one, it's time to take notice. Every single school of economics agrees that free trade makes a country prosperous and that any kind of tariff makes the nation poorer.

This isn't just economists from 200 years ago, or kooky Austrians working in Libertarian thinktanks or whatever. Economists across the board, from every school of thought, agree that tariffs make us worse off—a scientific consensus of the kind rarely seen in the field of economics.

The Initiative on Global Markets, or IGM, is a research organization that did a survey last year of numerous economists from many different universities and schools of economics. The statement they were asked to agree or disagree with was: "Adding new or higher import duties on products such as air conditioners, cars, and cookies — to encourage producers to make them in the US — would be a good idea." Not a single one of them agreed with the statement or even said they were uncertain; they all answered either "Disagree" or "Strongly Disagree." And this included economists from MIT, Yale, Berkeley, Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and others across the country. If they couldn't find a single economist to agree, then how can you justify it?

Interestingly, one of these economists was David Autor of MIT, who said: “Taxing consumers to subsidize domestic production is bad economics and a violation of the WTO agreement.” This is interesting because one of his papers, "The China Shock," is being actively misinterpreted as a promotion of tariffs and a refutation of free trade. What the paper actually found was that the labor market is high friction in places like Ohio and Michigan, due to things like unionization and high taxes, and this adversely affects industries where products can be imported from China. The economy can and will improve in the face of such a shock, but only if politicians allow it to and don't tax and regulate everything right and left. This is another example of government causing a problem and pointing the finger of blame somewhere else.

This is also the conclusion of a paper from the St. Louis Fed which found:

Also:

So that means you need to:

Let's think about this: tariffs make goods more expensive for Americans. If we are as generous to your side as we can possibly be, tariffs increase domestic employment (they don't, for reasons we've covered; at best it might boost a certain sector at the expense of others, but we'll grant it for the time being). But only a part of that additional price is going to go to the workers; the rest is absorbed in other costs of doing business.

Let's think about this: tariffs make goods more expensive for Americans. If we are as generous to your side as we can possibly be, tariffs increase domestic employment (they don't, for reasons we've covered; at best it might boost a certain sector at the expense of others, but we'll grant it for the time being). But only a part of that additional price is going to go to the workers; the rest is absorbed in other costs of doing business.

That being the case, why would it not be better to simply tax Americans that extra money and pay it directly to those would-be workers? And what is the moral difference?

I'll tell you one difference: tariffs are a regressive tax that disproportionately hurts the poor. That's what a paper published by the Center for Economic and Policy Research found:

This same effect applies to subsidies on exports. Yes, if you subsidize exports, more people in foreign countries will buy the exported goods. But think about what you're doing: you're taxing Americans so that foreigners can have cheaper products. It's exactly the same as if you'd taxed Americans to give money to foreigners so they can buy more stuff. And that helps us, how?

If you understand that, then you also see that you need to:

What we hear from a lot of politicians is that all of this is very well and good when there's free trade in both directions, but since foreign countries are putting restrictions on trade from the US, we need to put restrictions on them to stop them from hurting American consumers.

What we hear from a lot of politicians is that all of this is very well and good when there's free trade in both directions, but since foreign countries are putting restrictions on trade from the US, we need to put restrictions on them to stop them from hurting American consumers.

If you understand what I just said about subsidies, you'll understand why foreign subsidies are no reason to place tariffs. Foreign subsidies don't hurt Americans; they hurt the people in that country because they have to pay the taxes that go to the subsidies. It's exactly as if they forced their own citizens to pay for part of the price of the goods that we buy.

Conversely, if they place a tariff on our goods, they're only shooting themselves in the foot, for the same reason US tariffs end up costing Americans.

Politicians may crow about "unfair competition." Through subsidies or tariffs or currency manipulation or whatever, they make their goods so cheap that America just can't compete. But what that really does is allow Americans to have greater purchasing power: our paychecks now go further since many of the goods we buy are cheaper. The costs of all of this don't come from Americans somehow; the burden is placed on the people in that country in the form of higher taxes or inflation. "Unfair competition" really means "prices are advantageous to consumers, not producers," and that is the problem with protectionism: it's really about enriching cronies at the expense of the people.

Tariffs increase the price of foreign goods, meaning consumers will buy domestically. But why weren't they before? It must have been because the domestic goods cost too much. Ultimately, this is price manipulation that makes everyone poorer. Those crony industries may profit more in the short run, but in the long run, our economy isn't as prosperous as it otherwise would have been. "Protection" really means exploiting the consumer.

Prices—including the price of imported goods—convey information about how efficiently resources are being used. They give consumers valuable information about where their earnings would best be spent. And it goes the other way, too: by making decisions on whether or not to buy a certain good, consumers use the price mechanism to communicate information of their own. In this example, they're telling domestic producers not to produce so much of this particular good, and instead to divert those resources somewhere else where they can be put to better use. Insomuch as they are a conveyance of information, prices are a form of speech. And they are the most effective form of speech that consumers have with producers. Tariffs, subsidies, currency manipulations, and for that matter, any form of price control is, in a very real sense, a violation of our freedom of speech.

By the way, this video will be from an American perspective, but the concepts are universal and apply everywhere. So if you're somewhere else in the world, just replace "America" with your own country and it still applies.

This issue is very much tied in with economics, so fair warning: there's a good bit of economics in this video, but it's important. So here are the things you need to keep in mind if you want to support tariffs:

1. Understand the economics behind it.

In the supply/demand model, increased costs push the supply curve to the left, meaning that producers can't produce as many items of a certain good at each price level as they could before. This increases the equilibrium price while decreasing the equilibrium quantity.

In the supply/demand model, increased costs push the supply curve to the left, meaning that producers can't produce as many items of a certain good at each price level as they could before. This increases the equilibrium price while decreasing the equilibrium quantity.Tariffs are a cost that have to be added to the sale price of the imported good. So the only difference they'll make is in higher prices and fewer consumer goods sold.

The economic data backs this up. According to a 2008 paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research:

Long ago, Díaz Alejandro (1970) pointed out that if—like the Argentines—you double the price of a machine via trade barriers, then you are placing an enormous tax on investment and accumulation that will depress output. Historical evidence accords with his view...Where those barriers have dropped growth accelerations have been significantly higher than where barriers have remained. Some countries have reaped the benefits. More could yet do so and enjoy higher incomes and lower poverty rates...Essentially, you need to explain how making things more expensive helps Americans.

2. Learn the Law of Comparative Advantage.

In the early 19th century, economist David Ricardo posited the Law of Comparative Advantage. It's one of the few effects in economics that is accepted pretty much in every school of economics. To see how it works, let's simplify things a bit.

In the early 19th century, economist David Ricardo posited the Law of Comparative Advantage. It's one of the few effects in economics that is accepted pretty much in every school of economics. To see how it works, let's simplify things a bit.Let's say there are only two people in the world. Let's call them "Adam" and "Steve." They're going to need things to survive. We'll focus on two things: spears to hunt food, and axes to chop wood for fire and shelter.

Adam can make axes more easily than spears, and Steve can make spears more easily than axes. So they decide to have Adam make the axes and Steve make the spears. They then trade an axe for a spear. If that sounds like simple division of labor to you, you're absolutely correct. And if you're thinking you have all of the advantages that come from that, like specialization, you're also correct. But there are two counterintuitive things that Ricardo and others who built on his work observed.

Let's say Adam can make an axe in 3 hours and a spear in 4, and Steve can make a spear in 1 hour and an axe in 2. So Steve can make an axe and a spear in the same time it takes Adam to make just an axe. It may sound as if Steve doesn't need Adam and Adam's going to lose out, and a lot of policies—including tariffs—are made around this misunderstanding.

But it doesn't matter. If they make the trade, then Steve only has to work two hours making two spears; it's still beneficial for him to trade with Adam. By trading, Adam only has to work 6 hours instead of 7, and Steve only has to work 2 hours instead of 3. They both save an hour of labor, and so it's beneficial to make the trade, even if Steve is better overall at making both.

The second is that this doesn't just apply to cavemen making axes and spears. It applies to everyone in a modern economy, and—this is the important part—it applies to countries as well. If Japan is better at making cars than airplanes, and America is better at making airplanes than cars, then both countries are better off if America just makes planes to sell to Japan, and Japan just makes cars to sell to America. So in such a case, putting a tariff on cars hurts Americans.

Now, you might be thinking that it has to be equal for this to work out. If Americans buy lots of Japanese cars but Japan only buys a few airplanes, Americans will lose out. But the next thing you need to do is:

3. Give up the "Trade Deficit."

If America buys millions of Japanese cars but only sells hundreds of airplanes to Japan, you might call that a "trade deficit" and say it's a bad thing. This is just a non-starter of an argument. There is no such thing as a trade deficit.

If America buys millions of Japanese cars but only sells hundreds of airplanes to Japan, you might call that a "trade deficit" and say it's a bad thing. This is just a non-starter of an argument. There is no such thing as a trade deficit.Let's leave money out of it for a second. If we're trading airplanes for cars, then it just means that we'll trade (say) ten thousand cars for one airplane. Like Adam and Steve before, even if Japan can make an airplane for the same resources it can use to make ten thousand cars or even less, both countries are still better off making the exchange.

But it doesn't even have to be that way since countries are trading in their currencies. When Japanese want to buy an American plane, they need US dollars to do it, which means they'll have to give up some of their Japanese yen for them. And Americans who want to buy Japanese cars will need to give up some of their dollars for yen. And in the real world, of course, this happens across every product both countries trade.

For all the trade that's going on, if Japanese need 1 million dollars to buy American goods, and Americans need 1 million yen to buy Japanese goods, the exchange rate will be 1 dollar to 1 yen. But let's say there's a "trade deficit," where the amount of goods Americans buy from Japanese is more than what Japanese buy from Americans. So Americans need 2 million yen whereas Japanese still just need 1 million dollars. Now the exchange rate is 2 yen to 1 dollar. Any imbalance between trade is adjusted for by the exchange rate. And when government tries monkeying with the exchange rate, bad things happen, like in Venezuela.

But that's not what politicians are actually referring to when they talk about a trade deficit. They look at it after the exchange rate has taken place: where the exchange rate is still 2:1, but Japanese are buying less than 1 million dollars of American goods. You may be thinking, "Then what are they wanting the rest of the money for?" That is exactly the question you should ask—but it's one that politicians and the news media never seem to want to discuss.

There are only two things that can be done with money: it can be spent, or it can be invested. So if they don't want that money to purchase American goods, they must want it to invest in American capital. That means they'll be providing funds for businesses to expand, or for people to buy houses, or whatever. Investment is also known as deferred gratification, meaning in this case that Japanese are going to do less consuming, putting off some of that wealth until a later point in time, so Americans can take advantage of it.

Economists actually refer to a "trade deficit" as "net foreign investment." Because as long as exchange rates are free to fluctuate, any imbalance must be due to more investors in one country investing in the other than is going the other way. So whenever you use the term "trade deficit," understand that we see it for what it is: investment coming from other countries to expand our economy and our businesses, creating jobs and allowing us to produce more and have more for ourselves than we would have otherwise. They're doing without for a little while so that we can have more. You're going to have a very hard time convincing us that this is a bad thing.

In Chapter 6 of Economic Sophisms, Frédéric Bastiat wrote:

The truth is that we should reverse the principle of the balance of trade and calculate the national profit from foreign trade in terms of the excess of imports over exports. This excess, minus expenses, constitutes the real profit. But this theory, which is the correct one, leads directly to the principle of free trade...Assume, if it amuses you, that foreigners flood our shores with all kinds of useful goods, without asking anything from us; even if our imports are infinite and our exports nothing, I defy you to prove to me that we should be the poorer for it.Here's a beautiful refutation of the fallacy: Hong Kong has virtually no natural resources; it imports everything. What it does produce, like integrated circuits, is made with imported raw materials. They have a "trade deficit" of over $400 billion, almost twice their GDP. But Hong Kong is still a very prosperous nation, with the quality of life increasing by leaps and bounds, thanks to free trade, the world's freest market, and zero tariffs.

As the late Marc Allan Feldman said:

I have a trade deficit with my barber: I give him money; he cuts my hair. He never gives me money. Who cares? He cuts my hair.

4. Why do economists across the board believe they're bad?

There aren't many things that economists of every school believe. So when you do get one, it's time to take notice. Every single school of economics agrees that free trade makes a country prosperous and that any kind of tariff makes the nation poorer.

There aren't many things that economists of every school believe. So when you do get one, it's time to take notice. Every single school of economics agrees that free trade makes a country prosperous and that any kind of tariff makes the nation poorer.This isn't just economists from 200 years ago, or kooky Austrians working in Libertarian thinktanks or whatever. Economists across the board, from every school of thought, agree that tariffs make us worse off—a scientific consensus of the kind rarely seen in the field of economics.

The Initiative on Global Markets, or IGM, is a research organization that did a survey last year of numerous economists from many different universities and schools of economics. The statement they were asked to agree or disagree with was: "Adding new or higher import duties on products such as air conditioners, cars, and cookies — to encourage producers to make them in the US — would be a good idea." Not a single one of them agreed with the statement or even said they were uncertain; they all answered either "Disagree" or "Strongly Disagree." And this included economists from MIT, Yale, Berkeley, Harvard, Princeton, Stanford, and others across the country. If they couldn't find a single economist to agree, then how can you justify it?

Interestingly, one of these economists was David Autor of MIT, who said: “Taxing consumers to subsidize domestic production is bad economics and a violation of the WTO agreement.” This is interesting because one of his papers, "The China Shock," is being actively misinterpreted as a promotion of tariffs and a refutation of free trade. What the paper actually found was that the labor market is high friction in places like Ohio and Michigan, due to things like unionization and high taxes, and this adversely affects industries where products can be imported from China. The economy can and will improve in the face of such a shock, but only if politicians allow it to and don't tax and regulate everything right and left. This is another example of government causing a problem and pointing the finger of blame somewhere else.

This is also the conclusion of a paper from the St. Louis Fed which found:

China's trade shock resulted in a loss of 0.8 million U.S. manufacturing jobs, about 50 percent of the change in the manufacturing employment share unexplained by a secular trend. We find aggregate welfare gains but, due to trade and migration frictions, the welfare and employment effects vary across U.S. labor markets.In other words, those job losses were more than made up for by job and wage gains elsewhere. So when they point to the job losses in manufacturing, they're cherry-picking; they hope you look at this and blame it for part of the unemployment we're experiencing, but those job losses happened because that sector was less efficient. The result was that economic resources moved to other sectors that were more efficient, making life better for everyone in the country. You need to look elsewhere for a cause of unemployment, because this isn't one.

Also:

Our results indicate that although exposure to import competition from China reduces manufacturing employment, aggregate U.S. welfare increases."So the manufacturing sector might get a bit of a boost from tariffs, but the rest of us are worse off for it.

So that means you need to:

5. Explain how tariffs are better than straight-out welfare.

Let's think about this: tariffs make goods more expensive for Americans. If we are as generous to your side as we can possibly be, tariffs increase domestic employment (they don't, for reasons we've covered; at best it might boost a certain sector at the expense of others, but we'll grant it for the time being). But only a part of that additional price is going to go to the workers; the rest is absorbed in other costs of doing business.

Let's think about this: tariffs make goods more expensive for Americans. If we are as generous to your side as we can possibly be, tariffs increase domestic employment (they don't, for reasons we've covered; at best it might boost a certain sector at the expense of others, but we'll grant it for the time being). But only a part of that additional price is going to go to the workers; the rest is absorbed in other costs of doing business.That being the case, why would it not be better to simply tax Americans that extra money and pay it directly to those would-be workers? And what is the moral difference?

I'll tell you one difference: tariffs are a regressive tax that disproportionately hurts the poor. That's what a paper published by the Center for Economic and Policy Research found:

Tariffs—taxes on imported goods—likely impose a heavier burden on lower-income households, as these households generally spend more on traded goods as a share of expenditure/income and because of the higher level of tariffs placed on some key consumer goods.More specifically, the lowest income decile spends over 1.5% of after-tax household income on tariffs, compared to .6% for the second decile and less than .3% for the top decile. The burden is worse on families with children, especially single parents.

This same effect applies to subsidies on exports. Yes, if you subsidize exports, more people in foreign countries will buy the exported goods. But think about what you're doing: you're taxing Americans so that foreigners can have cheaper products. It's exactly the same as if you'd taxed Americans to give money to foreigners so they can buy more stuff. And that helps us, how?

If you understand that, then you also see that you need to:

6. Deal with the arguments against protectionism.

What we hear from a lot of politicians is that all of this is very well and good when there's free trade in both directions, but since foreign countries are putting restrictions on trade from the US, we need to put restrictions on them to stop them from hurting American consumers.

What we hear from a lot of politicians is that all of this is very well and good when there's free trade in both directions, but since foreign countries are putting restrictions on trade from the US, we need to put restrictions on them to stop them from hurting American consumers.If you understand what I just said about subsidies, you'll understand why foreign subsidies are no reason to place tariffs. Foreign subsidies don't hurt Americans; they hurt the people in that country because they have to pay the taxes that go to the subsidies. It's exactly as if they forced their own citizens to pay for part of the price of the goods that we buy.

Conversely, if they place a tariff on our goods, they're only shooting themselves in the foot, for the same reason US tariffs end up costing Americans.

Politicians may crow about "unfair competition." Through subsidies or tariffs or currency manipulation or whatever, they make their goods so cheap that America just can't compete. But what that really does is allow Americans to have greater purchasing power: our paychecks now go further since many of the goods we buy are cheaper. The costs of all of this don't come from Americans somehow; the burden is placed on the people in that country in the form of higher taxes or inflation. "Unfair competition" really means "prices are advantageous to consumers, not producers," and that is the problem with protectionism: it's really about enriching cronies at the expense of the people.

Tariffs increase the price of foreign goods, meaning consumers will buy domestically. But why weren't they before? It must have been because the domestic goods cost too much. Ultimately, this is price manipulation that makes everyone poorer. Those crony industries may profit more in the short run, but in the long run, our economy isn't as prosperous as it otherwise would have been. "Protection" really means exploiting the consumer.

Prices—including the price of imported goods—convey information about how efficiently resources are being used. They give consumers valuable information about where their earnings would best be spent. And it goes the other way, too: by making decisions on whether or not to buy a certain good, consumers use the price mechanism to communicate information of their own. In this example, they're telling domestic producers not to produce so much of this particular good, and instead to divert those resources somewhere else where they can be put to better use. Insomuch as they are a conveyance of information, prices are a form of speech. And they are the most effective form of speech that consumers have with producers. Tariffs, subsidies, currency manipulations, and for that matter, any form of price control is, in a very real sense, a violation of our freedom of speech.

Star Wars models for DAZ

Images of available Star Wars models for your 3D rendering. Note that these are not downloads but, where possible, download links will be on the pages. Some are hi-res characters and clothing for G8 and G3 models, some are simple objects such as vehicles. I'm hoping this will be a fairly exhaustive look at both free and premium models available for Star Wars fans.

$10/month

Separation of Medicine and State

This is something I've been thinking about a lot lately as we live through the COVID-19 pandemic. What's flabbergasting to me is that I see a lot of people claiming that this somehow disproves libertarianism and proves we need government. And it's flabbergasting because, as has been incredibly well-established, this only got as bad as it did because of government screw-ups, from the initial Chinese coverups to the WHO, as well as the CDC's screwed-up testing. But I don't want to talk about the screw-ups. I want to talk about how government interference in medicine prevented us from having the tools we need to mitigate and possibly even cure COVID-19. It's interesting that, from what I've seen, no one has even tried the whole canard about how our founding fathers never could have foreseen this situation when they wrote about our right to peaceably assemble. And I think it's because, even though no one says it, they deep down know the truth: our founders were very familiar with

Why Minimum Wage Proponents Are Pseudoscientists

By viewer request, I'm posting a transcript of my 2015 video "Why Minimum Wage Proponents Are Pseudoscientists." One small problem: the folder on my archive drive that houses the source files got corrupted, so I don't have access to the original graphics. I'll try to describe them as best as I can, but any confusion can be cleared up by watching the original video. So the Minimum Wage debate continues unabated. It doesn't matter that every school of economic thought except the Keynesians agree that Minimum Wage destroys jobs for the very people it's supposed to help. It doesn't matter that it's by far the consensus of labor economists. And it doesn't matter than I've completely destroyed the research showing small Minimum Wage increases having no disemployment effects. Why? Because to lift a phrase from James Randi, they're unsinkable ducks. They're just pseudoscientists peddling their bogosity for the sake of their own political gain, going against every principle of science along

Libertarianism and Property from First Principles

By popular demand, this is a transcript of my oft-referenced video, "Libertarianism and Property Rights from First Principles."

Here's the thing about logic: it's completely objective. There is no "my logic" or "your logic"; there's just logic. So if you have a logical position, then it's an objective argument that stems from First Principles.

First Principles are foundational propositions and axioms that do not have to be defended. As long as your argument is purely from First Principles, meaning that it's linked back to these First Principles with no breaks in the chain and no fallacious reasoning, then you don't actually need empirical e

Libertarians, Gary Johnson, and Election 2016

No, my candidate didn't win. But like all Libertarians, I can still feel good and hold my head high.

Because while the Republicans and Democrats have just faced their worst nightmare—a nightmare they face every four years—we Libertarians exist in a world of our own: one where principles matter, and where who we are is defined by them.

I voted against war and for peace. I voted against hatred, bigotry, envy, and division. I voted for both fiscal and personal responsibility. I voted for sound economics and mathematics. I voted to make America sane again.

My vote means that hundreds of thousands of dollars won't have to be spent i

© 2017 - 2024 shanedk

Comments1

Join the community to add your comment. Already a deviant? Log In

Well done! You might be interested in voluntaryism. I'm the webmaster for voluntaryist.com.

I watched your Youtube of this essay because a friend in the Voluntaryism Telegram group (t.me / voluntaryism_group) recommended it. He's been a subscriber for about 2 years, and he heard of you from "Mr Dapperton and Esoteric the Free."

Keep up the good work!